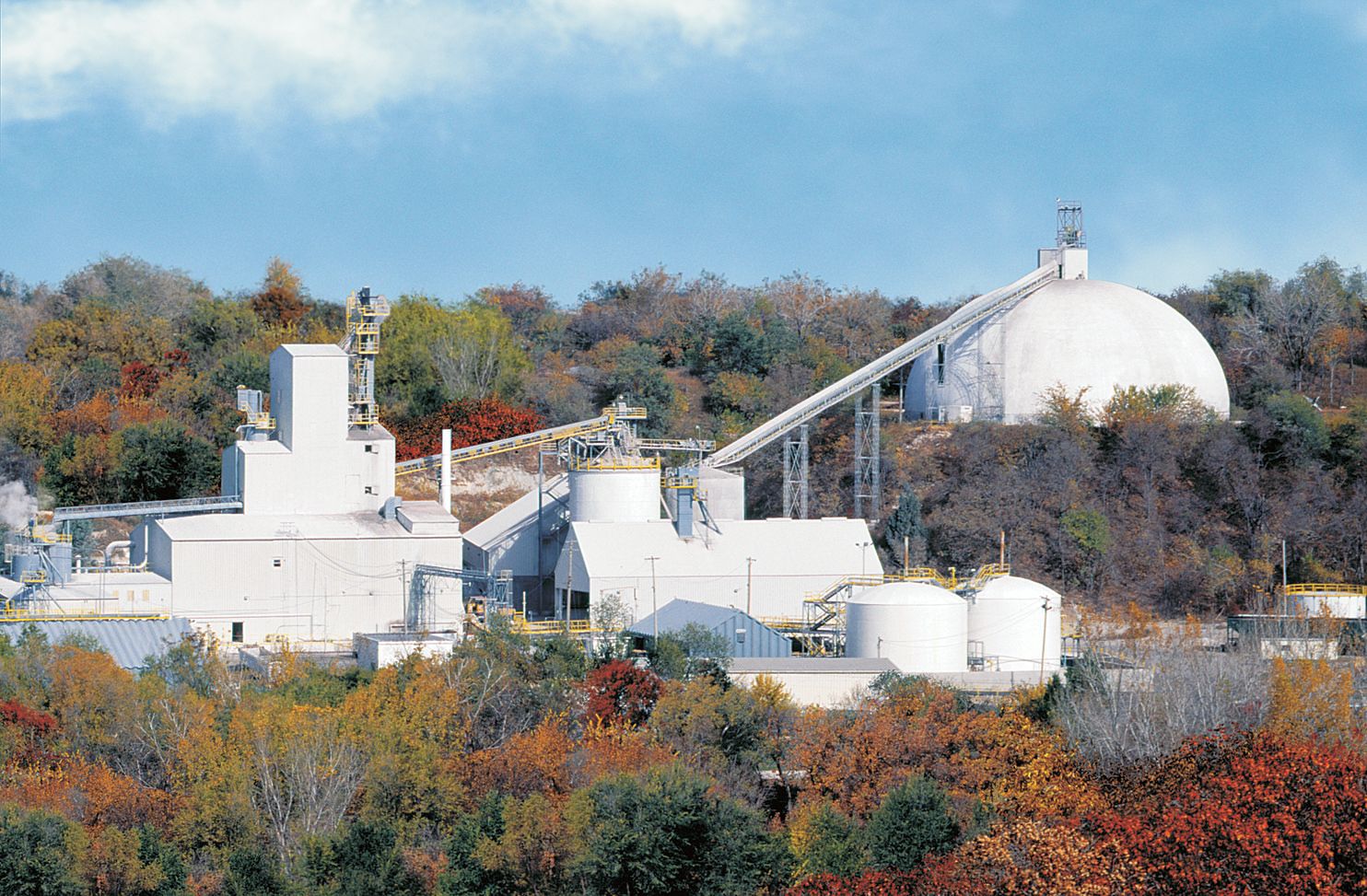

The legacy and evolution of safe potash mining in Saskatchewan

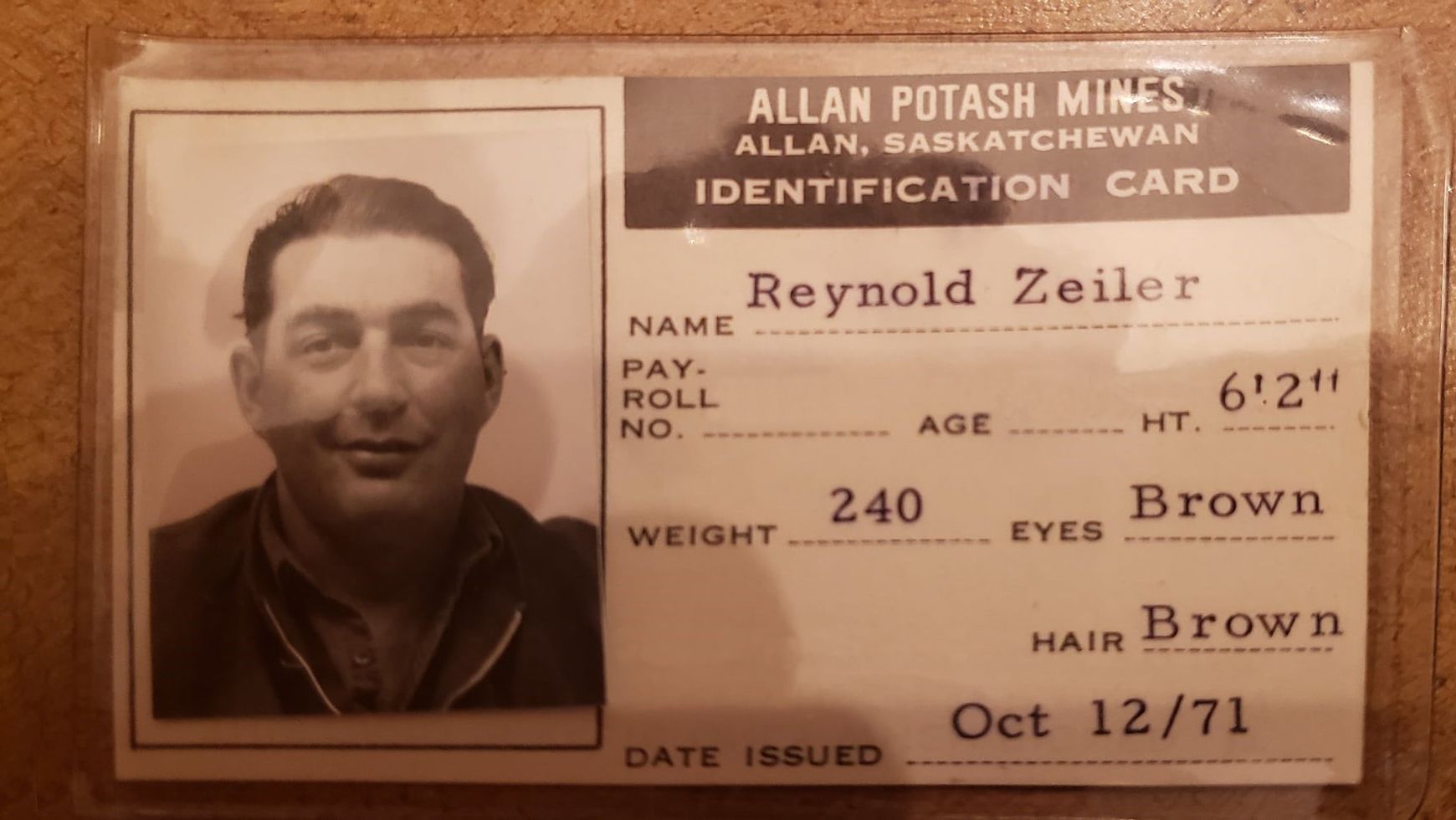

When Kelly Zeiler, Construction Supervisor, started working at our Allan Potash mine in 1977, he wasn’t the only Zeiler on site.

“My dad, Reynold, worked on the rigs at Allan when it was first built and helped with the shaft work, and he was still there when I joined,” says Kelly. “I’ve worked on the surface, underground, in loadout, in the warehouse and as a shaft foreman. I grew up with the people at Allan and we became like a big family.”

Reynold's identification card from 1971

Nutrien is a made-in-Canada company with deep roots in Saskatchewan, and the same can be said about Kelly. Born and raised in the province, he has managed a successful mining career at Allan spanning nearly five decades while also being a farmer – Feeding the Future at work and at home.

“I went to sleep the night after my first shift and woke up 47 years later,” he jokes. “This has been a good career – it’s helped me earn a living, raise four children with my wife, and enjoy our life here.”

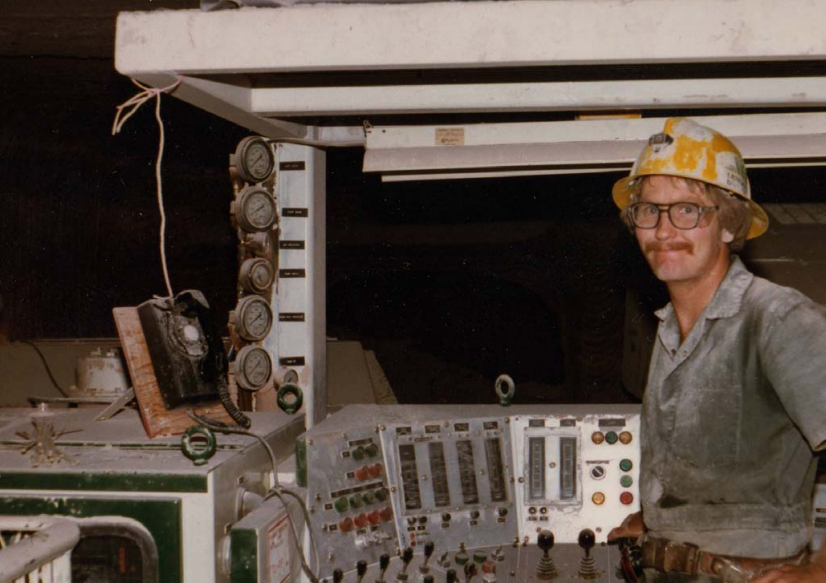

Kelly has seen a lot of changes throughout his career at the mine, especially in terms of safety.

“When I started working here, safety wasn’t the first thing we talked about. We tried to work as safely as we could with what we had, but at that time, we didn’t have the same resources as we do now,” he says. “Change management has also been a big part of it. We’re empowered to take the time to pause or stop a job that may be unsafe and come up with a sensible solution. There’s also been a lot of positive changes in terms of technology that’s helping to send our people home safe, every day.”

The changing landscape of mine safety

You may be surprised to learn that jackleg drills, which were first developed during the Industrial Revolution, are still used today in the mining industry for drilling in hard-to-reach areas. While some things never change, the safety culture at Nutrien’s potash mines has completely evolved.

Take fall protection, for example. 65 years ago, there weren’t minimum requirements for personal protective equipment (PPE). In the 1970s and 80s, the miner’s belt was introduced, followed by the five-point harness in the 90s. Our potash miners wear five-point harnesses with shock absorbers, trauma straps and self-retracting lanyards to protect them from potential falls or injuries.

“Mining doesn’t come without risks, so doing it safely is something to be proud of,” says Jason Belanger, Senior Safety & Health Manager, Potash. “The concept of a safe workplace is constantly evolving, making it crucial to foster a Culture of Care that emphasizes open communication, sharing and learning.”

In the 1960s and 70s, it was common to track only serious injuries and total recordable frequency rates. Significant progress came in 1972 when Saskatchewan became the first jurisdiction in Canada to pass health and safety legislation, followed by mining regulations in 1978. Since then, many new acts and regulations have been created to advance health and safety standards.

“We’re proud to work closely with occupational health and safety committees, encourage our workers to look out for each other and foster an environment where new ideas are welcomed,” says Jason. “Nutrien’s safety culture recognizes and prioritizes inclusion and mental health both at work and at home. While there is always more work to be done, it’s incredible to see how far we’ve come.”

A large part of the evolution of safety in potash mining has been due to automation. Our mine shafts and hoisting plants have gone through many iterations of upgrades. For example, the Lilly Controller – a hoisting engine controller developed in the early 1900s – initially used gravity systems and weights to control the hoists. Now, it’s fully automated thanks to programmable logic controller (PLC) systems.

In 2018, we introduced tele-remote technology at our Lanigan site, which has been helping improve personnel safety while also increasing productivity in the ore extraction process.

“When it comes to successful changes in technology and safety, it all starts with people and processes,” says Owen Gunther, Automation Project Lead. “Involving the right stakeholders at the right time has a significant impact because it ensures that our people are engaged and that our processes can evolve.”

This was the cover of a flyer used to communicate information about the Orebiter to Lanigan employees.

Digging up the past to inspire new ideas

Our earliest attempt at remote/automated mining dates back to 1979 with the Orebiter at our Lanigan site. The Orebiter was a prototype, intending to become a sophisticated automated mining unit. The project was put on hold indefinitely, largely due to being too complex for its time, but it was cited as an important learning lesson in future attempts at automation at the site.

The future of mining can be found across our six mines in Saskatchewan. By 2026, Nutrien is targeting to have 40-50 percent of potash ore tonnes cut by automation, not only to continue to enhance safety, but to also improve efficiency and productivity.

“Reflecting on the legacy of potash mining in Saskatchewan, it’s evident that the industry has undergone a remarkable transformation in terms of safety and technology,” says Jason. “From the early days when safety measures were minimal, to the present where automation and stringent safety protocols are the norm, the journey has been driven by the dedication and ingenuity of the people involved. Kelly Zeiler’s nearly five-decade-long career at the Allan mine epitomizes this evolution, showcasing how far we've come in prioritizing worker wellbeing and open communication.”

This photo of the Orebiter was used as a reference image in a presentation given nearly 30 years later.

Related stories